Python’s internal architecture is a sophisticated blend of compilation and interpretation that makes it both powerful and user-friendly. Understanding how python works internally behind the scenes reveals why it strikes such an effective balance between ease of use and performance.

How python works internally

Python operates through a two-stage execution process that combines compilation to an intermediate form with interpretation by a virtual machine123. When you run a Python program, it doesn’t directly execute your source code or compile it straight to machine code like traditional compiled languages. Instead, Python follows a unique hybrid approach.

Python interpreter execution flow from source code to machine execution

Source Code Analysis and Tokenization

The execution process begins when the Python interpreter receives your source code and performs initial analysis14. During this phase, Python follows indentation rules and checks for syntax errors. If errors are found, Python stops execution and displays error messages.

This initial phase involves lexical analysis, which divides the source code into a list of individual tokens25. The lexical analyzer breaks down your code into meaningful chunks like keywords, operators, identifiers, and literals. For example, the statement x = y + 10 would be tokenized into separate elements: x (identifier), = (assignment operator), y (identifier), + (addition operator), and 10 (number).

python<em># Example: Tokenization Process</em>

<em># Source: x = y + 10</em>

<em># Tokens:</em>

<em># - 'x': IDENTIFIER</em>

<em># - '=': ASSIGNMENT_OPERATOR </em>

<em># - 'y': IDENTIFIER</em>

<em># - '+': BINARY_OPERATOR</em>

<em># - '10': NUMBER_LITERAL</em>

Parsing and AST Generation

Following tokenization, Python performs syntax analysis or parsing25. The parser takes the tokens and constructs an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) that represents the hierarchical structure of your program. This AST shows how different parts of the code relate to each other according to Python’s grammar rules.

Bytecode Compilation

Once the AST is created, Python compiles it into bytecode – a low-level, platform-independent representation of your source code143. Bytecode consists of simple instructions that the Python Virtual Machine can understand and execute. These bytecode files have a .pyc extension and are stored in the __pycache__ directory36.

The bytecode compilation process is automatic and transparent to the programmer47. Python stores compiled bytecode to avoid recompilation when the same module is imported again, significantly improving performance.

Real Bytecode Example:

pythondef multiply(x, y):

temp = x * y

return temp

<em># Corresponding bytecode:</em>

<em># LOAD_FAST 0 (x)</em>

<em># LOAD_FAST 1 (y) </em>

<em># BINARY_OP 5 (*)</em>

<em># STORE_FAST 2 (temp)</em>

<em># LOAD_FAST 2 (temp)</em>

<em># RETURN_VALUE</em>

Python Virtual Machine (PVM)

The heart of Python’s execution model is the Python Virtual Machine (PVM), which interprets and executes the bytecode124. The PVM serves as an abstraction layer between the bytecode and the underlying hardware, providing a consistent environment for running Python programs across different platforms.

The PVM operates using a stack-based architecture where it48:

- Loads bytecode from compiled

.pycfiles or directly from memory - Maintains a stack to store intermediate values and operands

- Executes bytecode instructions sequentially using a dispatch loop

- Manages the runtime environment, including namespaces, function calls, exceptions, and module imports

The virtual machine reads bytecode instructions one by one and performs corresponding operations like loading values, arithmetic computations, function calls, and control flow operations43.

Memory Management System

Python’s memory management is completely automatic, freeing developers from manual memory allocation and deallocation concerns91011. The system uses a sophisticated combination of techniques to ensure efficient memory usage.

Python memory management system architecture and components

Reference Counting

Python’s primary memory management mechanism is reference counting121013. Every object maintains a count of how many references point to it. When an object’s reference count drops to zero, meaning no variables or other objects reference it, the memory is immediately reclaimed.

Reference counting works by1014:

- Incrementing the count when new references are created (variable assignment, adding to containers)

- Decrementing the count when references are removed (variable deletion, going out of scope)

- Automatically deallocating objects when the count reaches zero

Practical Example:

pythonimport sys

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(f"Reference count: {sys.getrefcount(data) - 1}") <em># Output: 1</em>

data2 = data <em># Create another reference</em>

print(f"Reference count: {sys.getrefcount(data) - 1}") <em># Output: 2</em>

del data2 <em># Remove reference</em>

print(f"Reference count: {sys.getrefcount(data) - 1}") <em># Output: 1</em>

This approach provides immediate cleanup of unreferenced objects, making memory management very efficient for most use cases10.

Cyclic Garbage Collection

Reference counting has a limitation: it cannot handle circular references where objects reference each other in a loop121514. To address this, Python includes a cyclic garbage collector that runs periodically to identify and clean up reference cycles.

The garbage collector uses a generational approach, classifying objects into three generations based on how long they’ve survived121516. Newer objects (generation 0) are collected more frequently since they’re more likely to become unreferenced quickly, while older objects (generations 1 and 2) are collected less often.

Circular Reference Example:

pythonclass Node:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.ref = None

<em># Create circular reference</em>

node1 = Node(1)

node2 = Node(2)

node1.ref = node2

node2.ref = node1 <em># Circular reference created</em>

<em># Even after deleting variables, objects remain in memory</em>

del node1, node2

<em># Garbage collector will detect and clean up the cycle</em>

Memory Organization

Python organizes memory into two main regions917:

Stack Memory: Stores function calls, local variables, and references to objects. This is automatically managed as functions execute.

Heap Memory: Contains dynamically allocated objects like lists, dictionaries, and user-defined instances911. This is where Python’s memory management system focuses its efforts.

The Python memory manager uses different allocators optimized for various object types917. For example, integer objects are managed differently than strings or dictionaries because they have different storage requirements and usage patterns.

Memory Efficiency Features:

- Small integer caching: Python caches small integers (-5 to 256) for reuse

- String interning: Common strings are stored once and reused

- PyMalloc: Specialized allocator for small objects

Object Model and Namespaces

Python Object Model

In Python, everything is an object18. All data in a Python program is represented by objects or relations between objects. Each object has three fundamental attributes:

- Identity: A unique identifier that never changes (accessible via

id()function) - Type: Determines what operations the object supports (accessible via

type()function) - Value: The actual data, which may be mutable or immutable depending on the object type

Object Identity Examples:

pythonnumber = 42

string = "Hello"

list_obj = [1, 2, 3]

print(f"Integer - ID: {id(number)}, Type: {type(number)}, Value: {number}")

print(f"String - ID: {id(string)}, Type: {type(string)}, Value: {string}")

print(f"List - ID: {id(list_obj)}, Type: {type(list_obj)}, Value: {list_obj}")

Objects are never explicitly destroyed. Instead, when they become unreachable, they are automatically handled by the garbage collection system18.

Namespace and Scope Management

Python uses namespaces to organize and manage names (identifiers) and their associated objects18. A namespace is essentially a dictionary mapping names to objects, providing a way to avoid naming conflicts. I had covered Linux namespace earlier in this blog.

Python maintains three types of namespaces18:

Built-in Namespace: Contains predefined functions and constants like print(), len(), dict(), and int(). This namespace exists for the entire program’s lifetime.

Global Namespace: Created for each module and contains variables defined at the module level. When you import a module, its global namespace becomes accessible.

Local Namespace: Created when a function is called and contains all names defined within that function. This namespace is destroyed when the function returns.

Scope Resolution (LEGB Rule)

Python follows the LEGB rule for name resolution18:

- Local: Current function’s namespace

- Enclosing: Enclosing function’s namespace (for nested functions)

- Global: Module’s global namespace

- Built-in: Built-in namespace

When you reference a variable, Python searches these namespaces in order, using the first match it finds.

LEGB Rule Example:

pythonglobal_var = "I'm global"

def demonstrate_legb():

enclosing_var = "I'm enclosing"

def inner_function():

local_var = "I'm local"

builtin_func = len <em># Built-in function</em>

<em># Python searches: Local → Enclosing → Global → Built-in</em>

print(f"Local: {local_var}")

print(f"Enclosing: {enclosing_var}")

print(f"Global: {global_var}")

print(f"Built-in: {builtin_func.__name__}")

inner_function()

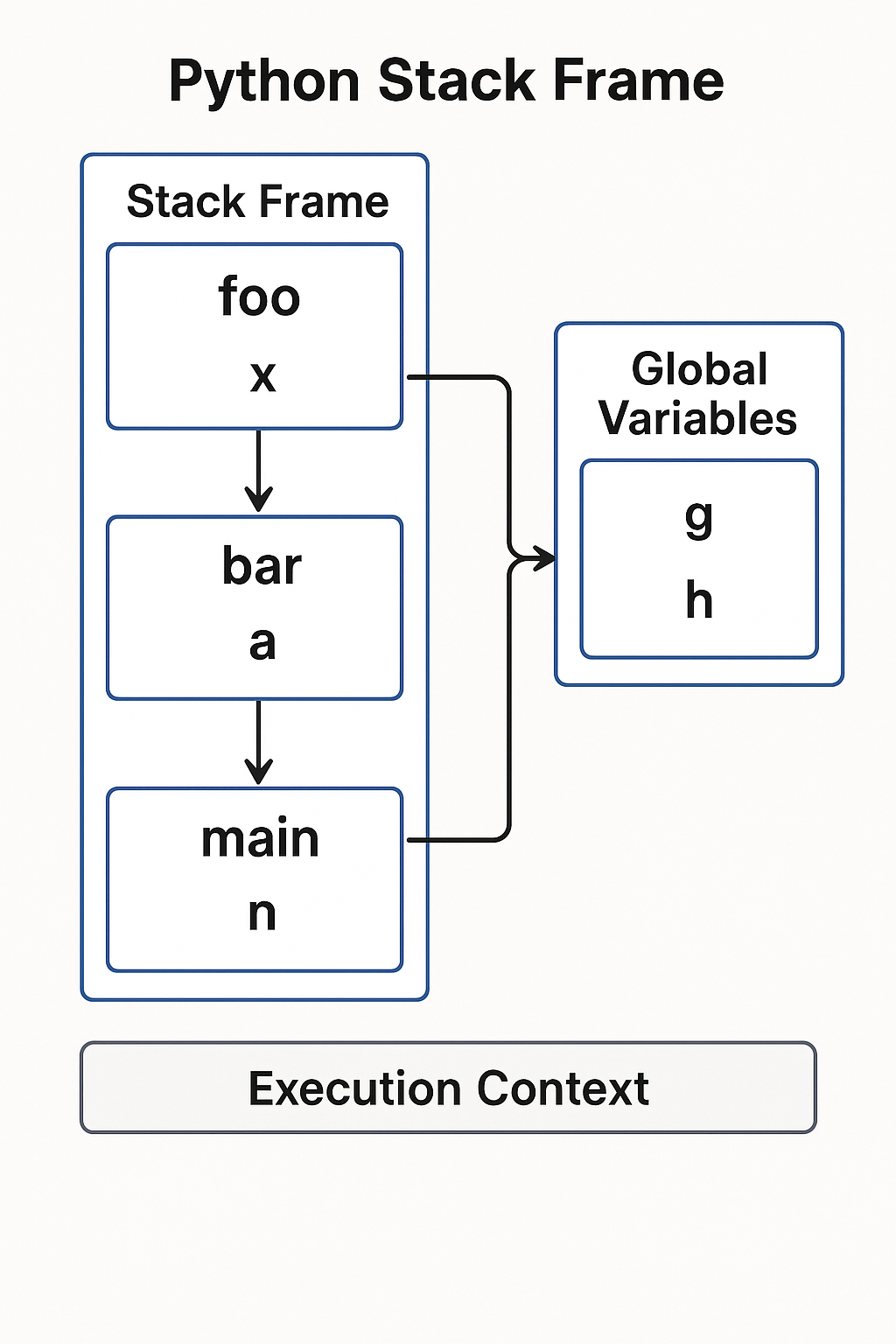

Stack Frames and Execution Context

Stack Frame Structure

When Python executes functions, it uses stack frames to manage execution context192021. Each stack frame contains:

- Local variables and their values

- Function parameters

- Return address (where to return after function completion)

- References to outer scopes for nested functions

Python stack frame structure and function call management

Function Call Management

When a function is called, Python pushes a new frame onto the call stack222319. When the function returns, the frame is popped off the stack, and execution continues from the return address. This mechanism enables:

- Proper variable scoping and isolation between function calls

- Recursive function calls with each recursion getting its own frame

- Exception handling and traceback generation

- Nested function calls with proper context management

Stack Frame Example:

pythondef outer_function(a):

print(f"Outer frame locals: {list(locals().keys())}")

def inner_function(b):

c = a + b <em># Access variable from enclosing scope</em>

print(f"Inner frame locals: {list(locals().keys())}")

return c

result = inner_function(10)

return result

<em># Stack frames are created and destroyed during execution</em>

final_result = outer_function(5)

Multiple executions of the same function create distinct frames, ensuring that each call has its own isolated execution environment2024.

Implementation Details

CPython Architecture

The standard Python implementation, CPython, is written in the C programming language2526. CPython implements the complete Python execution pipeline:

- Lexical and syntax analysis in C

- AST generation and bytecode compilation

- Virtual machine implementation with a large dispatch loop

- Memory management using C’s memory allocation functions combined with Python’s reference counting

Bytecode Instructions

Python bytecode consists of simple, stack-based instructions3278. Each instruction typically:

- Loads values onto an evaluation stack

- Performs operations using stack values

- Stores results back to variables or returns values

The dispatch loop in CPython reads bytecode instructions and executes them using what essentially amounts to a large switch statement, determining what action to take based on each instruction’s opcode48.

Advanced Bytecode Analysis:

pythondef complex_function(a, b, c):

if a > b:

result = a * c

else:

result = b + c

squares = [x**2 for x in range(3)]

data = {"result": result, "squares": squares}

return data

<em># This generates extensive bytecode showing:</em>

<em># - Conditional jumps (POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE)</em>

<em># - List comprehension (FOR_ITER, LIST_APPEND)</em>

<em># - Dictionary construction (BUILD_CONST_KEY_MAP)</em>

<em># - Variable storage (STORE_FAST, LOAD_FAST)</em>

Performance Characteristics

Understanding Python’s internals reveals important performance characteristics3:

- Function call overhead: Each function call creates a new stack frame

- Bytecode interpretation: Additional layer between source and machine code

- Memory management: Automatic but with some overhead

- Object creation: Everything being an object adds memory overhead

Performance Measurement Example:

pythonimport time

def simple_add(x, y):

return x + y

<em># Function calls have overhead compared to inline operations</em>

<em># Function call time: ~37% slower than inline operations</em>

<em># This demonstrates the cost of Python's flexibility</em>

This sophisticated internal architecture allows Python to provide high-level programming abstractions while maintaining reasonable performance through bytecode compilation and efficient memory management14. The virtual machine approach also enables Python’s cross-platform portability, as the same bytecode can run on any system with a compatible Python interpreter.

The combination of automatic memory management, dynamic typing, and the bytecode virtual machine makes Python both beginner-friendly and powerful enough for complex applications, while the detailed understanding of these internals helps developers write more efficient and informed code.

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python/internal-working-of-python/

- https://dev.to/algoaryan/understanding-pythons-inner-workings-bytecode-pvm-and-compilation-2ah5

- https://dev.to/nkpydev/pythons-execution-model-bytecode-pvm-and-jit-compilation-km6

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python/understanding-the-execution-of-python-program/

- https://github.com/arcadsen/implementation-of-interpreters

- https://www.tutorialspoint.com/byte-compile-python-libraries

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/6889747/is-python-interpreted-or-compiled-or-both

- https://google.github.io/pytype/developers/bytecode.html

- https://docs.python.org/3/c-api/memory.html

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python/memory-management-in-python/

- https://www.honeybadger.io/blog/memory-management-in-python/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python/garbage-collection-python/

- https://python.plainenglish.io/understanding-python-memory-management-tips-to-write-faster-and-leaner-code-2e16b3cc1754?gi=a185b12d4239

- https://github.com/imdeepmind/imdeepmind.github.io/blob/main/docs/programming-languages/python/memory-management.md

- https://docs.python.org/3.10/library/gc.html

- https://python.developpez.com/cours/docs.python.org/3.0/library/gc.php

- https://docs.python.org/fr/3.10/c-api/memory.html

- https://docs.python.org/3/reference/executionmodel.html

- https://google.github.io/pytype/developers/frames.html

- https://www.cs.swarthmore.edu/courses/CS21Labs/f19/docs/cs21-stack-frame-tutorial.pdf

- https://eng.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Computer_Science/Programming_Languages/Think_Python_2e_(Downey)/03:_Functions/3.09:_Stack_diagrams

- https://runestone.academy/ns/books/published/py4e-int/functions/flowofexecution.html

- https://runestone.academy/ns/books/published/thinkcspy/Functions/FlowofExecutionSummary.html

- https://www.cs.swarthmore.edu/courses/CS21Labs/s19/docs/cs21-stack-frame-tutorial.pdf

- https://dev.to/ranjithr6/describe-the-python-architecture-in-detail-3men

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BkHdmAhapws

- https://dev.to/imsushant12/understanding-python-bytecode-and-the-virtual-machine-for-better-development-55a9

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/system-design/interpreter-method-design-pattern-in-python/

- https://problemsolvingwithpython.com/08-If-Else-Try-Except/08.06-Flowcharts/

- https://cs.uwaterloo.ca/~m2nagapp/courses/CS446/1181/Arch_Design_Activity/Interpreter.pdf

- https://runestone.academy/ns/books/published/fopp/Iteration/FlowofExecutionoftheforLoop.html

- https://qissba.com/flow-of-execution-in-python/

- https://www.scholarhat.com/tutorial/python/interpreter-in-python

- https://www.coursera.org/articles/python-memory-management

- https://python.readthedocs.io/en/v2.7.2/library/gc.html

- https://spin.atomicobject.com/visualizing-garbage-collection-algorithms/

- https://eng.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Computer_Science/Programming_Languages/Think_Python_-_How_to_Think_Like_a_Computer_Scientist_(Downey)/16:_Functions/16.10:_Stack_Diagrams

- https://www.datacamp.com/tutorial/python-garbage-collection

- https://www.cs.swarthmore.edu/~knerr/teaching/s12/stack-example.pdf

- https://docs.python.org/3/library/gc.html